When speaking a new language, you’ll find that many things about it are different compared to the language you’re used to. Sounds, words, grammar, everything is…foreign? Well, yes, of course.

But maybe you haven’t yet thought about whether or not the sentence structure and word order are different, too.

First of all, what do we mean by that? We’re talking about the basic word order, the correct sequence of all the elements that form the basic structure of a sentence.

If you compare the English and Italian sentence structure, you’ll definitely find differences that might create some confusion, especially when you get to negative sentences, questions, and complex phrases. But don’t worry about it; we’re here to help you with this simple guide. We’ll help you understand the basics of Italian word order rules, and then we’ll guide you until you’re able to perform well when creating more advanced sentences.

So, are you ready to learn about word order in Italian?

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- The Basics of Italian Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

- Il Buono, il Brutto e il Cattivo: Italian Word Order with Modifiers

- The Importance of Exercising

- The Famous Last Words

1. The Basics of Italian Word Order with Subject, Verb, and Object

The basic Italian sentence structure, as with all Neo-Latin languages, follows the Subject – Verb – Object (SVO) pattern.

(And by the way, since we’ll be talking a lot about apples…what about checking out how to say the names of all kinds of fruit?)

First of all, let’s see what the single elements of this sentence mean:

- {Eva mangia una mela.} (“Eva eats an apple.”)

Subject = It’s who/what is doing the action >> Eva mangia una mela.

Verb = It’s the action >> Eva mangia una mela.

Object = It’s the destination of the action >> Eva mangia una mela.

The sentence structure doesn’t change, even if you want to make the same sentence interrogative. In fact, in Italian, there is no S-V inversion as there is in other European languages (French and German, for example), and you don’t need to add anything to the sentence as you would do in English.

In the case of Italian question word order, the basic sentence structure remains the same; you just need to add the interrogative tone and the question mark.

Eva, are you really going to eat that…???

See the examples:

- {Eva mangia una mela.} (“Eva eats an apple.”)

- {Eva mangia una mela?} (“Does Eva eat an apple?”)

- {Studi l’italiano.} (“You study Italian.”)

- {Studi l’italiano?} (“Do you study Italian?”)

Notice how in Italian, we generally omit the personal pronoun as a subject (io, tu, lui/lei, noi, voi, loro – “I, you, he/she, we, you, they”) unless there’s an ambiguity in the sentence, or you want to give particular emphasis to the person doing the action.

But what happens when you want to make a negative sentence? Very simple. You add the negative adverb non in front of the verb:

- {Eva non mangia una mela.} (“Eva does not eat an apple.”)

- {Eva non mangia una mela?} (“Doesn’t Eva eat an apple?”)

- {Non studi l’italiano.} (“You don’t study Italian.”)

- {Non studi l’italiano?} (“Don’t you study Italian?”)

As you can see, whether it’s affirmative or interrogative doesn’t change the structure of the sentence.

This is always the basic structure, even when the sentence becomes more complicated. For example, you could have a whole clause as a subject:

La prima donna che abita sulla terra mangia la mela. (“The first woman living on earth eats the apple.”)

Similarly, you could have a whole clause as an object:

Eva mangia quel frutto rosso o giallo o verde che chiamiamo mela. (“Eva eats that red or yellow or green fruit that we call apple.”)

2. Il Buono, il Brutto e il Cattivo: Italian Word Order with Modifiers

Let’s look at the word order in Italian sentences when things get more complex. What happens to the sentence when you add, for example, an adjective that modifies the nouns (like bravo or “good”), or an adverb that modifies the verb (like sempre or “always”). These are called modifiers, as they’re used to add meaning—and therefore modify—the element they go with.

1. Adjectives

- {Lo studente studia l’italiano.} (“The student studies Italian.”)

What if I want to add that we’re talking about an “American” student (americano) studying Italian?

- {Lo studente americano studia l’italiano.} (“The American student studies Italian.”)

Did you see what happened? The adjective went after the noun. And this is the general rule: Italian adjectives follow the noun:

L’italiano non è una lingua (noun) difficile (adjective). (“Italian is not a difficult language.”)

Ho comprato un vestito rosso. (“I bought a red dress.”)

Sei un ragazzo simpatico! (“You are a nice boy!”)

But all rules have an exception, right? So, keep in mind that some of the most common Italian adjectives are placed before the noun. And here’s the list:

| bello | “beautiful” | Un bel* ragazzo | “A beautiful boy” |

| bravo | “good” | Una brava ragazza | “A good girl” |

| brutto | “ugly,” “bad” | È un brutto giorno | “It’s a bad day” |

| buono | “good” | Hai fatto un buon* lavoro. | “You did a good job.” |

| caro | “dear” | Sono dei cari amici. | “They are dear friends.” |

| cattivo | “bad” | Non dare il cattivo esempio. | “Don’t set a bad example.” |

| giovane | “young” | Conosco un giovane attore. | “I know a young actor.” |

| grande | “big” | Abbiamo una grande opportunità. | “We have a great opportunity.” |

| lungo | “long” | Facciamo una lunga passeggiata. | “Let’s take a long walk.” |

| nuovo | “new” | Il nuovo libro è rosso. | “The new book is red.” |

| piccolo | “small,” “little” | Ho un piccolo problema. | “I have a small problem.” |

| stesso | “same” | La stessa ragione | “The same reason” |

| vecchio | “old” | Un vecchio albero | “An old tree” |

| vero | “true” | È una vera avventura! | “It’s a real adventure!” |

*Bello/a and buono/a (“beautiful” and “good”), when they come before a noun, change their endings following the same rules of the definite article (bello >> il) and the indefinite article (buono >> un). Check the following examples. Do you want to know more and practice?

Un bel bambino/Un bambino bello! (“A cute baby!”)

- Il ragazzo >> il bel ragazzo

- Lo studente >> il bello studente

- Un giorno >> un buon giorno

- Uno studente >> un buono studente

But watch out! If they’re used together with an adverb, they must follow the noun, as in the general rule:

- È un vecchio albero. (“It is an old tree.”) | È un albero molto vecchio. (“It is a very old tree.”)

- È un brutto giorno. (“It’s a bad day.”) | È un giorno veramente brutto . (“It’s a really bad day.”)

The same thing happens if you want to convey emphasis or express a contrast. In the following sentence, for example, the stress of the sentence is on the age of the tree, and not the tree itself:

- Questo non è un albero vecchio, è un albero giovane! (“This is not an old tree, it is a new tree!”)

2. Adverbs

Just like adjectives, adverbs are modifiers and they appear in a sentence to slightly modify the meaning of the verb or adjective they go with. In Italian, they’re usually placed after the verb:

- Leggo sempre il giornale. (“I always read the newspaper.”)

- John parla bene l’italiano. (“John speaks Italian well.”)

Naturally, there are some exceptions to this rule in case of:

- Modifying an adjective

- È un albero molto vecchio. (“It is a very old tree.”)

- È un albero molto vecchio. (“It is a very old tree.”)

- Modifying another adverb

- John parla molto bene l’italiano. (“John speaks Italian very well.“)

- John parla molto bene l’italiano. (“John speaks Italian very well.“)

- The negative non, which we’ve already seen

- Non leggo il giornale. (“I don’t read the newspaper.”)

But notice what happens if you add another negative adverb. Let’s compare English to Italian: Double negatives are grammatically incorrect in English, but in the Italian language, they’re perfectly acceptable:

- Non leggo mai il giornale. (“I never read the newspaper.”)

- Non leggo più il giornale. (“I no longer read the newspaper.”)

- Non leggo quasi mai il giornale. (“I almost never read the newspaper.”)

Do you think we can add some more elements to complicate the structure a bit? Certamente! (“Of course!”) Which brings us to the other exception, when an adverb is formed with the -mente suffix (usually equivalent to the English “-ly” suffix).

I always read the newspaper. Do you?

See, for example, the case of normalmente (“generally, normally”):

- A) Normalmente non leggo il giornale.

- B) Non leggo normalmente il giornale.

- C) Non leggo il giornale normalmente.

All these sentences have the same meaning (“I don’t normally read the newspaper”), although we can argue that by moving around the adverb, we end up stressing different parts of the sentence. In A), the stress is on the frequency; in B), it’s on the act of reading; in C), it’s on the newspaper. It’s a small nuance, but nevertheless is there.

3. Adverbs & Auxiliary or Modal Verbs

So far, we’ve looked at simple verbs. But what happens if a verb is composed of an auxiliary, as in the case of the passato prossimo, or with modal verbs (potere, volere, sapere, dovere – “can, will, know, must”)?

With these verbs, you normally follow the general rule. But in the presence of the following adverbs expressing time, assessment, certainty, or doubt, they can be placed in the middle, between the auxiliary and the past participle (or between the modal verb and the infinitive).

| Ancora (“Yet”) | Proprio (“Really”) |

| Appena (“Just”) | Subito (“Immediately”) |

| Finalmente (“Finally”) | Certamente (“Surely”) |

| Già (“Already”) | Forse (“Maybe”) |

| Mai (“Never”) | Nemmeno (“Not even”) |

| Sempre (“Always”) | Probabilmente (“Probably”) |

| Spesso (“Often”) | Sicuramente (“Definitely”) |

- Eva ha appena mangiato la mela… (“Eva just ate the apple…”)

- Non ho ancora letto il giornale. (“I haven’t read the newspaper yet.”)

- Voglio sicuramente studiare l’italiano con ItalianPod101. (“I definitely want to study Italian with ItalianPod101.”)

- Devo proprio chiedere scusa…? (“Do I really have to apologize…?”)

4. Prepositional Phrases

In most sentences, we end up referring to “when,” “where,” and “how” the action is taking (or took) place. These sentences are the ones that explain the when, where, and how, and they’re called prepositional phrases since they’re often introduced by a preposition.

- Studio l’italiano di sera. [when?] (“I study Italian in the evening.”)

- Studio l’italiano a Firenze. [where?] (“I study Italian in Florence.”)

- Studio l’italiano con ItalianPod101. [how?] (“I study Italian with ItalianPod101.”)

As you can see in the examples above, these phrases normally go at the end of the sentence, although with most of the phrases indicating the time aspect of the action (when?), you can safely move the elements around, just as you would in English:

- Studio l’italiano di sera. [when?] (“I study Italian in the evening.”)

- Di sera studio l’italiano. [when?] (“In the evening, I study Italian.”)

- A pranzo non bevo mai il caffè. [when?] (“For lunch, I never have coffee.”)

- Non bevo mai il caffè a pranzo. [when?] (“I never have coffee for lunch.”)

But, if you’re not sure, always place them at the end of the sentence, and you’ll definitely be correct.

If you want more information on Italian prepositions, be sure to take a couple of minutes to watch the video below:

5. Personal Pronouns

Remember the first sentences we looked at?

- {Eva mangia una mela.} (“Eva eats an apple.”)

- {Studi l’italiano.} (“You study Italian.”)

Subject, verb, object. In that order. Well…not always. If you substitute the object with a personal pronoun, that pronoun would still be the object of the action, but it goes BEFORE the verb. Take a look:

- {Eva la mangia in fretta.} (“Eva eats it in a hurry.”)

- {Lo studi con ItalianPod101.} (“You study it with ItalianPod101.”)

Help! I need a Personal [pronoun] Trainer!!!

The same rules apply to indirect personal pronouns, as in:

- Gli chiedo un favore. (“I ask a favor of him.”)

- Mi piace la pizza. (“Pizza pleases me.“= “I like pizza.”)

This is also true for the little pronouns ci (“in it,” “there”) and ne (“of it”).

- A Roma? Ci andiamo domani. (“To Rome? We go there tomorrow.”)

- Ha del prosciutto? Ne vorrei 100 grammi. (“Do you have ham? I would like 100 grams of it.”)

Things, however, change a little when we have these same pronouns, but the verb is an infinitive, a gerund, or an imperative. (Maybe you need a little more practice with those tenses or how they’re conjugated?

Because with these tenses, the pronoun can be placed either before or after. And in case it’s after, you need to attach it to the verb. Let’s see how:

- {Eva mangia una mela.} (“Eva eats an apple.”)

- {Eva la mangia in fretta.} (“Eva eats it in a hurry.”)

- {“Eva, mangiala!} (“Eva, eat it!”)

- {Studi l’italiano.} (“You study Italian.”)

- {Lo studi con ItalianPod101.} (“You study it with ItalianPod101.”)

- {Puoi studiarlo con ItalianPod101.} (“You can study it with ItalianPod101.”)

A little patience and lots of exercise: the perfect strategy for learning a language!

3. The Importance of Exercising

Time to put everything into practice with these step-by-step exercises on Italian word order. Let’s start with a very basic sentence, and we’ll add up elements of complexity. Check the sections above in case you’re uncertain of something.

How would you translate these sentences?

- “Mary studies Italian.” – ________________________________________________________

- “She studies it with ItalianPod101.” – _____________________________________________

- “She studies Italian with ItalianPod101 everyday.” – __________________________________

- “Her friends don’t study Italian with ItalianPod101 yet.” – ______________________________

- “She studies Italian with ItalianPod101 everyday comfortably at home.” – _________________

- “Maria never forgets her Italian lessons.” – _________________________________________

- “Maria has probably studied Italian today.” – _____________________________________

- “This summer, Maria can study it in Florence.” – ______________________________________

Check your answers here:

1. Maria studia l’italiano.

2. Lo studia con ItalianPod101.com.

3. Studia l’italiano con ItalianPod101 ogni giorno.

4. I suoi amici non studiano ancora l’italiano con ItalianPod101.

5. Studia l’italiano con ItalianPod101 ogni giorno comodamente a casa.

6. Maria non dimentica mai le sue lezioni di italiano.

7. Maria ha probabilmente studiato l’Italiano oggi.

8. Quest’estate Maria può studiarlo a Firenze.

4. The Famous Last Words

Now you’ve learned how to structure a sentence in Italian. Soon, with a little practice, you’ll be able to build more and more complex sentences, putting every word in the correct order. Hopefully, this guide has helped you with this mission.

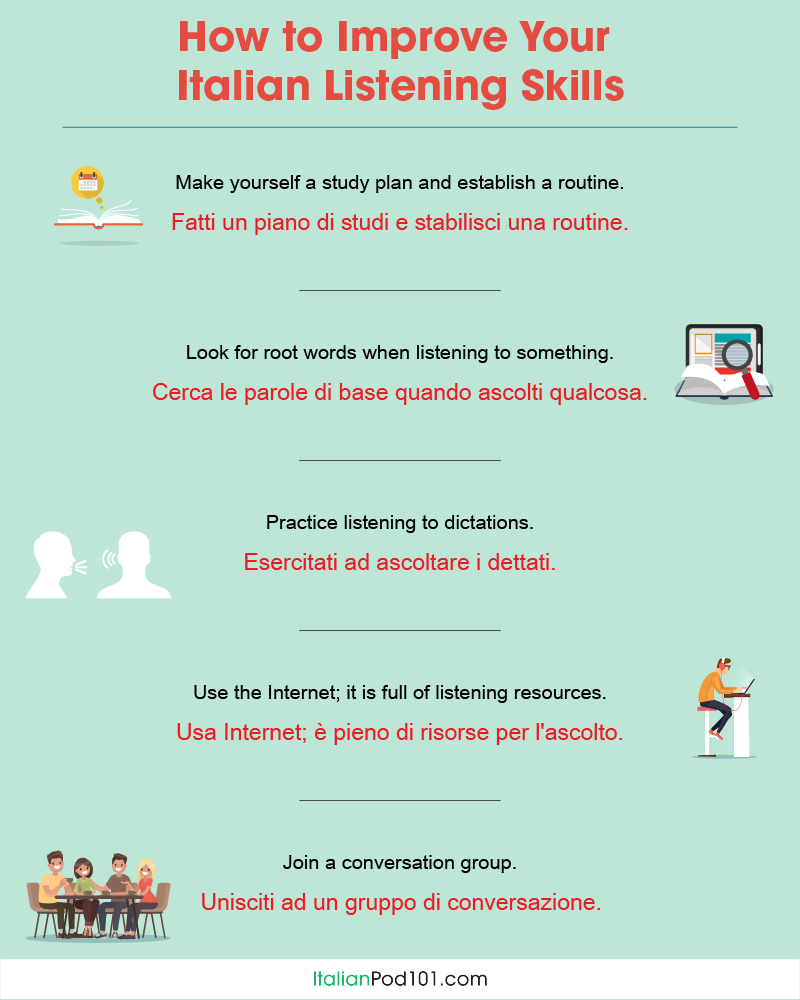

Practice is always the best strategy for improving Italian grammar, vocabulary, and communication skills. So make sure you visit ItalianPod101.com. Here you’ll find a great number of free resources, podcasts, lessons, and even mobile apps and a free PDF with practical and efficient lessons. Keep up with your good work on your Italian learning!

In the meantime, if there’s anything in this lesson you didn’t quite understand, feel free to leave us a comment and we’ll do our best to help you out!